Changes in Personality Traits Predict Early Career Outcomes

Post by Shireen Parimoo

What's the science?

Are conscientious people more likely to be satisfied with their career? Several studies show that career outcomes are associated with personality traits. For example, traits like emotional stability and conscientiousness are related to higher income and occupational attainment. Although these traits are largely stable aspects of our personality, they also tend to vary across different life stages, suggesting that our personality undergoes changes over the course of our lifetime. It is particularly important to understand the nature of personality growth in early adulthood because it is a critical period in career development. This week in Psychological Science, Hoff and colleagues investigated how personality changes from late adolescence to early adulthood are related to various career outcomes.

How did they do it?

The authors followed two large, nationally representative samples of adolescents in Iceland (Sample 1 N = 485, Sample 2 N = 1290), beginning when participants were students (15-17 years old) to when they were young adults (27-29 years old). During this period, they measured participants’ personality traits at three (Sample 1) and five time points (Sample 2) using the NEO Five-Factor Inventory, a personality test that provides scores on the traits of openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and emotional stability. They used linear growth-curve analysis to assess participants’ baseline scores in adolescence on each personality trait and the rate at which their scores changed over time.

After approximately 12 years, the authors recorded subjective career outcomes such as job and career satisfaction, as well as objective measures like monthly income, highest degree obtained, and occupational prestige. Occupational prestige was based on the most recent job held by the participants. To rate occupations on status and prestige, they used the online tool O*NET that classified jobs into different titles (e.g., surgeon) and assigned each title a rating on various work-value dimensions like Achievement and Recognition. To investigate the relationship between personality changes and career outcomes, the authors specified a separate path model (a statistical approach) for each outcome, including personality traits as predictors and controlling for the effect of gender.

What did they find?

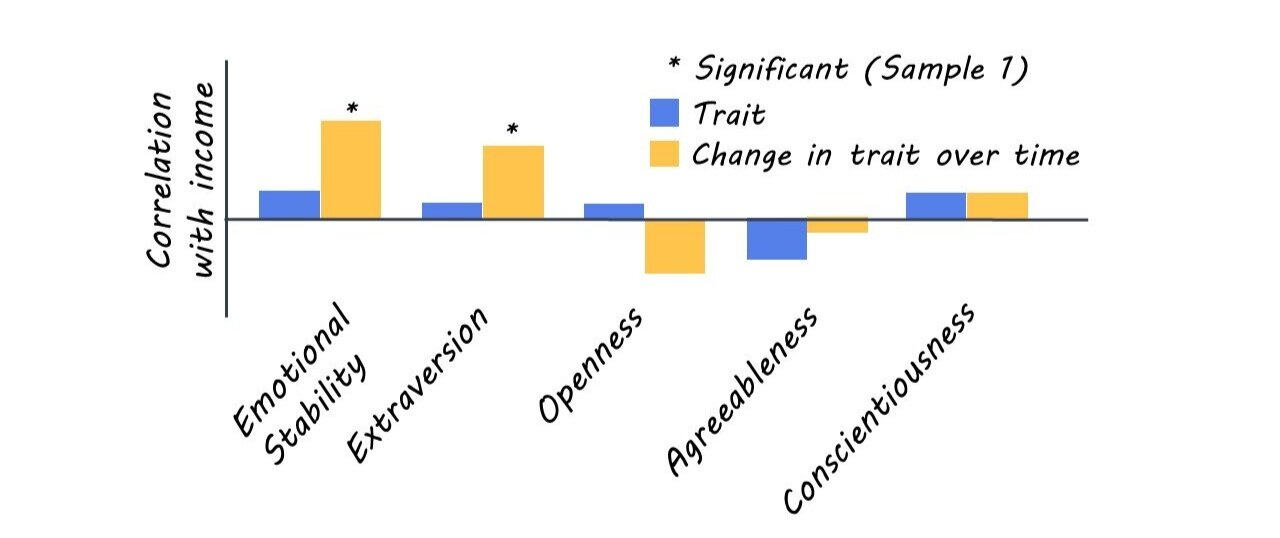

Agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness increased with age, whereas emotional stability did not change, and extraversion scores decreased. Higher conscientiousness, emotional stability, and agreeableness in adolescence were associated with higher degree attainment in the future. Similarly, baseline levels of emotional stability and conscientiousness (Sample 1) as well as openness and extraversion (Sample 2) were related to greater future occupational prestige. In fact, emotional stability and conscientiousness in adolescence were positively related to nearly all career outcomes, highlighting their importance in future career development. Moreover, changes in personality traits were also predictive of career outcomes. For example, higher income and career satisfaction were associated with increases in emotional stability from adolescence to young adulthood. Similarly, although extraversion decreased in general, increases in extraversion were related to higher career and job satisfaction. Overall, these results show that personality traits in adolescence predict objective measures of career success whereas certain changes in personality traits over time are linked to subjective career outcomes.

What's the impact?

These results are exciting because they highlight both enduring and mutable aspects of personality development in the transition from adolescence to adulthood. In addition, this is the first longitudinal study to demonstrate how personality traits in adolescence and young adulthood predict objective and subjective career outcomes, respectively. Future research can further examine the direction of the relationship between personality changes and career success.

Hoff et al. Personality Changes Predict Early Career Outcomes: Discovery and Replication in 12-Year Longitudinal Studies. Psychological Science (2020). Access the original scientific publication here.