How Neurons in the Human Brain Encode the “When” of Experiences

Post by Meagan Marks

The takeaway

Neurons in the medial temporal lobe help distinguish temporal patterns within recurring experiences, influencing the implicit prediction of future events and guiding subsequent behavior.

What's the science?

Whether performing a daily routine or learning a new task, the human brain is constantly integrating aspects of experience—specifically, the “what” (objects/events), “where” (spatial location), and “when” (temporal structure)—to create a cohesive understanding of the world.

Temporal structure—the “when” of an experience—allows the brain to organize information based on order in time. Encoding information in such a manner is crucial to memory formation, sequential learning, and decision making. By recognizing subtle sequences and patterns in time, the brain can predict future outcomes and adapt behavior accordingly. This process is needed for everyday tasks, like comprehending the words on a book page or responding to the flow of ideas during a conversation.

Temporal structure is vital for survival and success, but the specific neuronal mechanisms behind this cognitive process remain unclear. This week in Nature, Tacikowski and colleagues explore how neurons encode the temporal structure of experiences into memory by observing the neural activity of human participants.

How did they do it?

To determine how human neurons encode temporal structure, the authors recruited 17 participants, all of whom had intracranial electrodes implanted for clinical reasons. The authors then recorded the activity of individual neurons within the medial temporal lobe (MTL)—a region of the brain known for its role in memory and spatial cognition. A complex behavioral task was also created to ensure that subtle temporal patterns were presented to the participants as neuronal activity was recorded.

The behavioral task consisted of three phases. During the first, participants were repeatedly shown six images of people that elicited a strong response from neurons in the MTL. These images were displayed at random and participants were asked to identify the gender of each person shown.

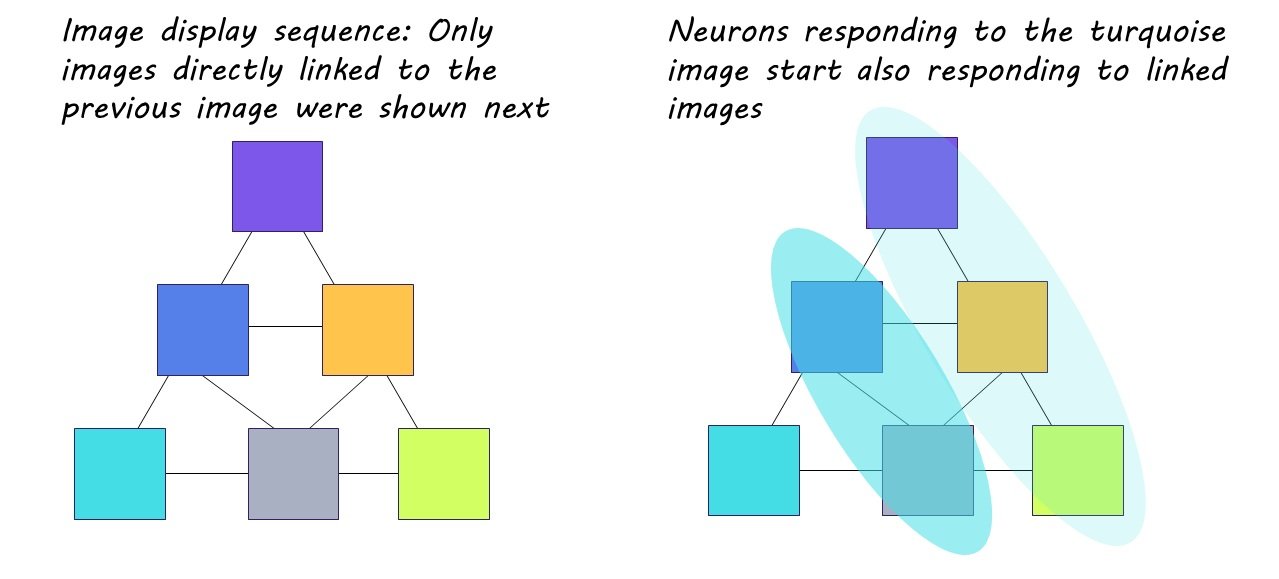

During the second phase, the same six images were repeatedly presented over the course of six trial rounds, but this time in a predetermined sequence. This sequence was based on a pyramidal structure established behind the scenes, where one image was assigned the top of the pyramid, two were assigned to the middle, and three were assigned to the bottom. Although the participants were only shown one image at a time, these images were shown in alignment to this pyramidal arrangement, so that only images “touching” each other on the pyramid could follow each other in the display line up. During these trials, the participants were engaged in a separate task—determining if the images had been flipped—and were not aware of the display pattern.

The third and final phase mimicked the first, however, the participants had been sufficiently exposed to the display sequence.

What did they find?

During the first phase of the behavioral experiment, the researchers noticed that certain neurons in the MTL exhibited a significantly stronger response to one particular image compared to the others. As the experiment progressed, these neurons adjusted their activity based on the display pattern. With continued exposure, some of the initially selective neurons began responding more strongly to images that were connected on the pyramid to the original image they had favored (i.e., images connected within the sequence). This strengthening of neuronal activity directly aligned with exposure to the pattern, indicating that these adaptable neurons made associations between images and embedded the sequence into memory. The sequence was even ‘replayed’ by the neurons spontaneously during study breaks, strengthening the memory of the pattern. These neurons were distributed across the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex, suggesting that the hippocampal-entorhinal system plays a key role in encoding temporal structure.

Participants also exhibited delayed behavioral responses in the final phase when an image broke the learned sequential pattern. Given that participants remained unaware of the display pattern, it can be inferred that their recognition and memorization of the sequence occurred largely implicitly.

What's the impact?

This study is the first to show that neurons in the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex work together to encode the temporal structure of experience. These neurons play a crucial role in recognizing and memorizing patterns, influencing the implicit prediction of future events, and guiding subsequent behaviors. These findings offer a deeper understanding of the neuronal mechanisms that underlie human behavior and experience.