The Choice to Socialize Prevents Drug Addiction in Rats

Post by Deborah Joye

What's the science?

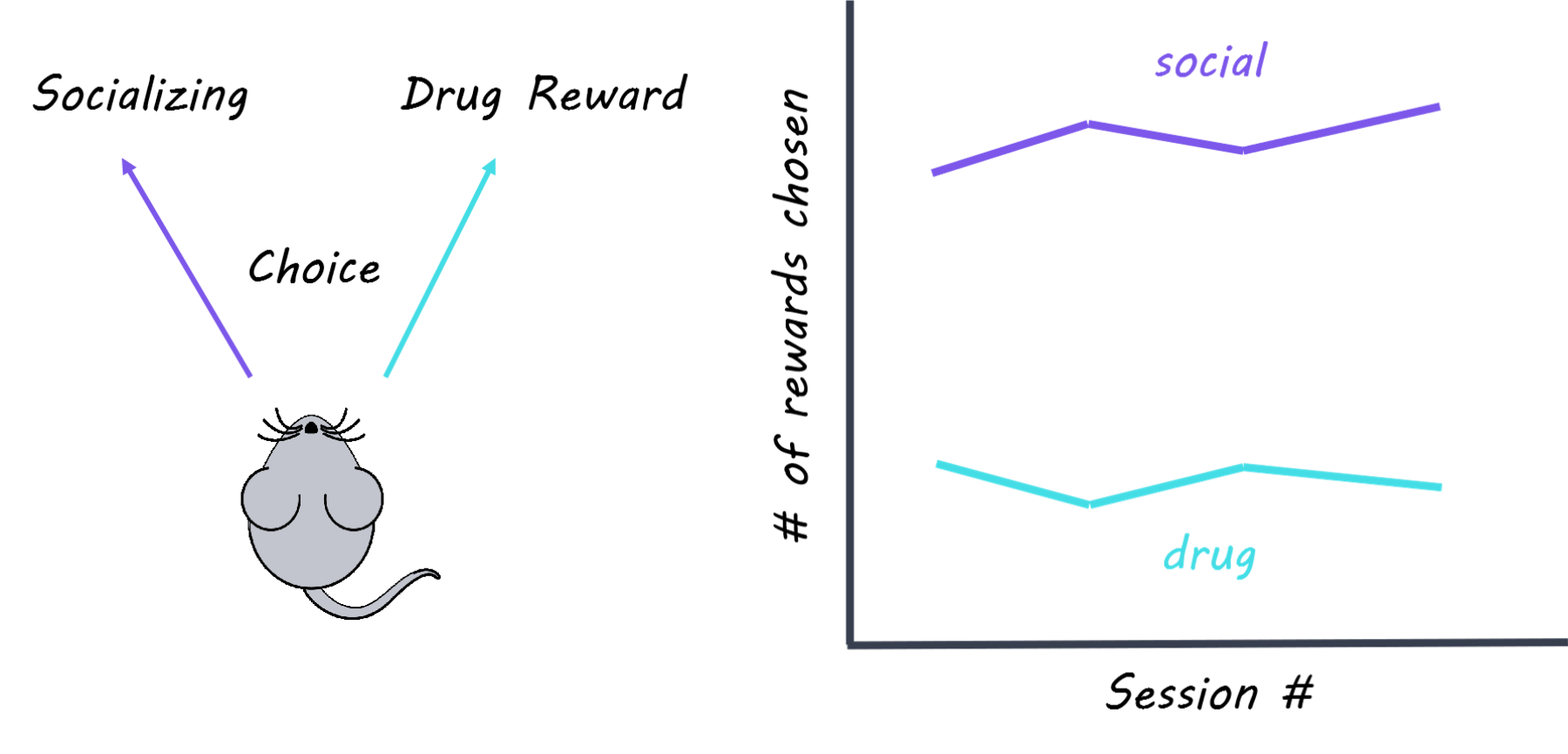

There are very few treatment options for human addiction, despite the large amount of animal research on addiction mechanisms. One reason might be because the impact of social cues on drug use is not fully considered. For example, we know that rodents and monkeys will choose a good-tasting food over drugs. But for humans, social rewards are more likely than food rewards to protect against drug use. Research shows that rodents housed in groups are less likely to take drugs in the first place, and less likely to relapse if they have taken drugs in the past. Typically, social environments and drug use in animal studies are controlled by the experimenter. If the rats could control their choice between taking drugs or socializing, what would they choose? This week in Nature Neuroscience, Venniro and colleagues use operant conditioning to demonstrate that rats will choose a social reward over drug use regardless of the type of drug, the strength of drug, how long they’ve been taking drugs, and how long they’ve been abstinent.

How did they do it?

The authors used operant conditioning to train rats so that pressing a certain lever resulted in social time with another rat, while pressing a different lever resulted in an infusion of drug (methamphetamine or heroin depending on the experiment). They also measured how often rats hit an “inactive” lever which didn’t do anything, to make sure that rats weren’t randomly hitting levers. The choice between drugs or socializing was mutually exclusive, meaning that rats could only choose one or the other but not both. The authors performed several manipulations to see how the rats’ choices might change: they administered different drug dosages, progressively increased the time delay between lever pressing and socializing; punished social choice with a small shock; and compared rats based on their motivation to seek the drug (addiction score: high, medium, low). The authors then either removed access to drugs (forced abstinence) or let rats choose (i.e. voluntary) between drug and alternative non-drug rewards (either food or social ) then tested if rats were more or less likely to relapse into drug use. In relapse tests, rats were abstinent from drugs for some period, and then reintroduced to the environment they associated with drug use. Generally, the longer a rat had not had drugs, the more drug-seeking behavior they showed in a drug-related environment, a phenomenon called “incubation of craving.” Finally, to probe the underlying neural mechanisms, the authors tested whether different forms of abstinence (forced v. voluntary) were associated with changes in neuronal activity in brain regions involved in drug-seeking and relapse, such as the amygdala and insular cortex. Specifically, they used immunohistochemistry (which labels proteins) and in situ hybridization (which labels RNA) to visualize which cells were activated during a relapse test.

What did they find?

The authors found that rats trained to take drugs would consistently choose a social reward over drugs regardless of drug dosage and addiction score. Rats returned to taking drugs only when the social reward was delayed or punished. Rats that chose socializing over drug use showed less drug-seeking behavior in a relapse test, even if social choice and access to drugs were removed for a month. This suggests that social reward can be protective against incubation of craving and future relapse. Rats that were given the food reward choice showed more drug-seeking behavior in a relapse test than rats given the social reward choice, suggesting that socializing is more rewarding than food. Lastly, the authors found that rats who chose socializing over drugs had increased activation of inhibitory cells in the lateral portion of the central amygdala (protein kinase C-delta (PKCδ)-expressing cells), and decreased activation of the insular cortex. In contrast, rats that were forced into abstinence showed increased activation of different populations of cells associated with drug craving (somatostatin-expressing cells in the lateral central amygdala and output neurons in the medial central amygdala). These findings suggest that cells in the amygdala are recruited to block activity associated with drug craving and relapse while rats are socializing.

What's the impact?

This study is the first to show that when rats are given the choice between socializing or using drugs, rates of drug abstinence are almost 100%. These findings highlight the necessity of considering social factors when investigating the neuroscience of addiction and suggest that social reward is a better drug-alternative model than food reward. Finally, this study demonstrates that positive social interactions protect against addictive behaviors and addiction-related changes in the brain, which has significant implications for clinical treatment options for human addicts.

Venniro et al. Volitional social interaction prevents drug addiction in rat models. Nature Neuroscience (2018). Access the original scientific publication here