Working Memory Performance in Childhood is Related to Frontoparietal Activity

Post by Shireen Parimoo

What's the science?

Working memory is the ability to store and manipulate information in mind; it is crucial for complex cognitive behaviors like reasoning, problem-solving, and planning that facilitate daily functioning. Working memory develops throughout childhood and adolescence, and peaks in adulthood before declining in older age. It is supported by cognitive processes like attention and executive functions that activate regions of the brain’s frontoparietal network, which includes regions such as the lateral prefrontal cortex. However, the link between working memory, other cognitive processes, and the neural activity supporting those processes in childhood has not been well-established. This week in Journal of Neuroscience, Rosenberg and colleagues used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and a battery of cognitive tasks to investigate the relationship between working memory and a range of cognitive processes.

How did they do it?

Participants were 11,537 children between 9-10 years old who were part of the longitudinal Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study. In the first year, the children completed several tasks while undergoing fMRI scanning and outside the scanner. These tasks assessed a range of cognitive functions such as working memory (list sorting task), recognition memory, fluid intelligence (matrix reasoning task), language abilities (e.g. picture vocabulary test), and attention (e.g. flanker task), among others. The in-scanner tasks included an emotional n-back task with high (2-back) and low (0-back) working memory loads, a monetary incentive delay task measuring reward processing, and the stop-signal task assessing inhibitory control. Participants also performed a recognition memory task outside the scanner for the stimuli presented during the emotional n-back task. To better understand the relationship between working memory and other cognitive functions, the authors first correlated performance on the list-sorting task with performance on the other behavioral tasks.

To characterize relationships between working memory and brain activity related to different cognitive processes, the authors next related working memory performance on the list sorting task to fMRI activity observed during the in-scanner tasks. To isolate the contribution of working memory to task-related activity, they examined the contribution of non-working memory processes to neural activity observed during the three in-scanner tasks. For example, they contrasted activity in response to neutral and emotional stimuli in the n-back task, which allowed them to examine how brain activity related to emotion regulation is related to working memory performance. Finally, these analyses were performed while controlling for variables such as age, sex, fluid intelligence, and testing site to ensure that the results were not driven by confounding variables.

What did they find?

Working memory performance was strongly related to language skills, fluid intelligence, attention, as well as performance on the emotional 2-back task. Importantly, these associations were significant even after controlling for age, sex, and other confounding variables. Interestingly, reward processing and inhibitory control were not strongly related to working memory performance, although that could be attributed to low task reliability of the reward processing task. Together, these results highlight the link between working memory and a wide variety of cognitive functions in late childhood.

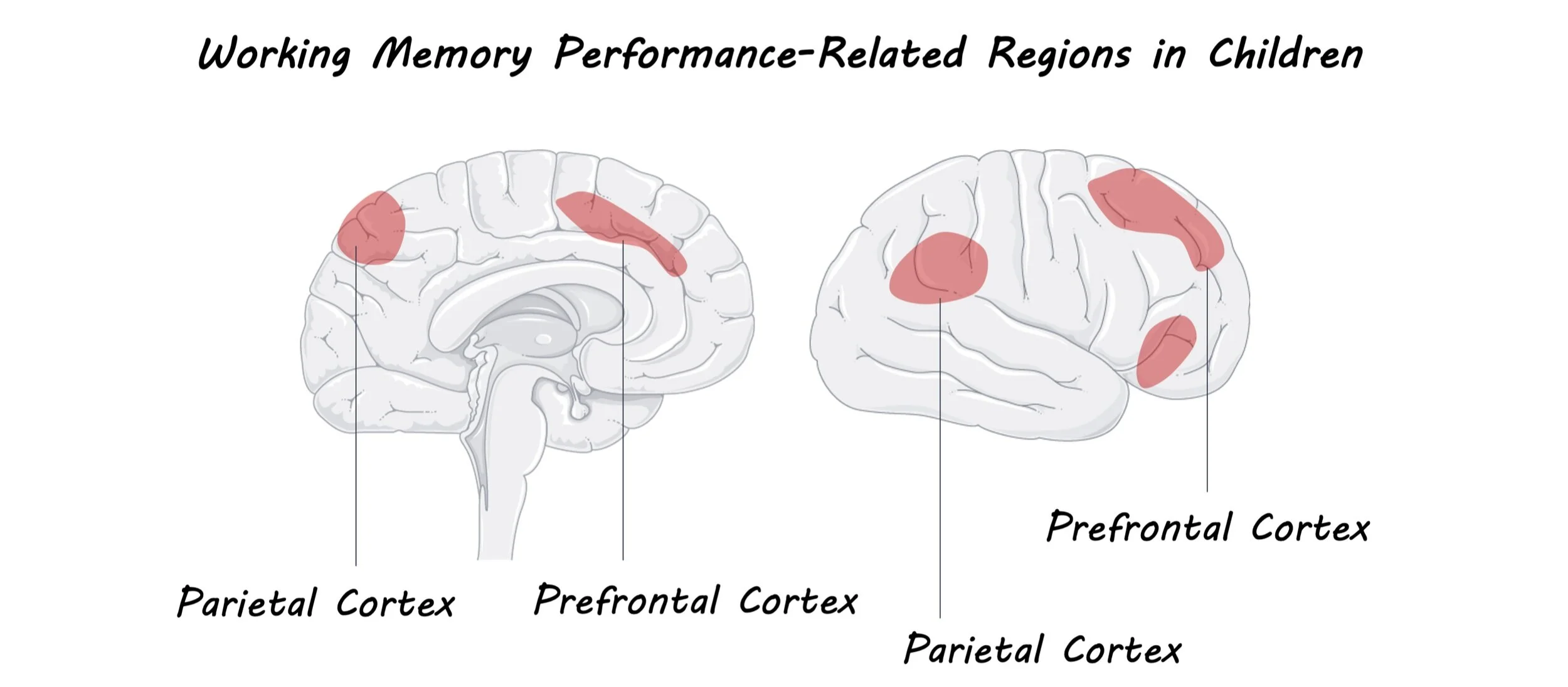

Higher working memory performance on the list-sorting task was related to greater activation of regions in the frontoparietal control network like the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the precuneus during high memory load 2-back relative to low-load 0-back blocks of the emotional n-back task. This was particularly the case at high memory load in the 2-back task compared to the low-load 0-back task, indicating that children activate similar regions under high working memory load as adults. In other words, children with stronger working memory abilities showed greater frontoparietal network activation during a more challenging working memory task compared to children with weaker working memory abilities.

What's the impact?

This study is the first to comprehensively detail the association between individual differences in working memory, cognitive processes, and fMRI activity on multiple cognitive tasks in a large developmental sample of participants. The finding of working memory-specific frontoparietal activation opens up exciting avenues for future research to use this as a marker to explore differences in working memory ability across a diverse range of populations.

Rosenberg et al. Behavioral and neural signatures of working memory in childhood. Journal of Neuroscience (2020). Access the original scientific publication here.