Psilocybin Reduces Depressive Symptoms by Reorganizing Functional Brain Networks

Post by Shireen Parimoo

The takeaway

Psilocybin, a psychedelic drug commonly known as magic mushrooms, is increasingly viewed as a viable treatment option for psychiatric conditions like major depression. It reduces the severity of depressive symptoms by reorganizing the functional connectivity of brain networks.

What's the science?

Major depressive disorder is commonly treated using serotonin-selective reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) that increase serotonin concentrations in the brain. Psychedelic drugs like psilocybin are now being considered viable options for treating major depression as they also increase serotonin levels. In the brain, serotonin receptors are present in many brain regions, including brain regions that comprise the default mode (DMN) and executive control/salience networks (E/SN). The DMN is generally active during self-referential thinking and is over-activated in individuals with depression, while the E/SN are associated with attentional processes that are impaired in depression. One possibility is that psilocybin alters the functional properties of these networks by acting on serotonin receptors in the brain. This week in Nature Medicine, Daws and colleagues used clinical and resting-state fMRI (rs-fMRI) data from two clinical trials to investigate the effects of psilocybin treatment on brain network organization and depressive symptoms.

How did they do it?

The authors used data from two clinical trials on psilocybin treatment for major depressive disorder: an open-label trial with 16 treatment-resistant patients who knew they would receive psilocybin treatment, and a double-blind randomized-controlled trial (DB-RCT) with patients who either received psilocybin or an SSRI. Although the patients in the DB-RCT did not know which treatment they received, they were informed that they would either receive a high dose or a negligible dose of psilocybin. In both trials, participants underwent rs-fMRI scanning and completed the Beck Depression Inventory I for an assessment of their depressive symptoms. The authors used functional connectivity analyses to identify the extent to which brain networks were integrated or segregated from each other. Lastly, they estimated the dynamic flexibility of the networks (i.e., how often different brain regions switched network membership over time) in the DB-RCT.

In the open-label trial, participants were given one low dose of psilocybin and a higher dose one week later. A clinical assessment and rs-fMRI scan were performed at baseline (prior to the first dose) and one day after the second dose of psilocybin. Clinical follow ups were also conducted three and six months after the second dose to examine the long-term effect of psilocybin treatment on depression. In the DB-RCT, participants underwent clinical assessments and scanning followed by psilocybin or SSRI treatment at baseline and three weeks later. They also took a daily capsule with psilocybin, placebo, or the SSRI for six weeks following the first dose. Finally, clinical follow-ups were conducted two weeks, four weeks, and six weeks after the first dose.

What did they find?

Psilocybin treatment reduced depressive symptom severity in both the short-term (1-6 weeks) and in the long-term (3-6 months) across both clinical trials. Moreover, in the DB-RCT, psilocybin was found to be more effective than the SSRI treatment. In both trials, there was an increase in the global integration of the brain's functional networks that followed psilocybin therapy. The increase in connectivity between the brain's networks correlated with improvements in the long-term well-being of patients. There were no observed changes in the global integration of the brain networks in patients who received the SSRI treatment.

Digging deeper, the brain's higher-order networks that are associated with cognition and the flexible adaptation of behaviour showed significant changes after psilocybin. This was expected because these networks house the highest densities of serotonin receptors and function abnormally in depression. In the open-label trial, the DMN was less segregated and more integrated with the E/SN one day after treatment. This means that psilocybin reduced the extent to which DMN regions were connected to each other and increased their connectivity with regions of the E/SN. In the DB-RCT, greater dynamic flexibility of the E/SN was associated with greater symptom improvements after receiving psilocybin. Again, these changes were not observed in patients who received the SSRI treatment.

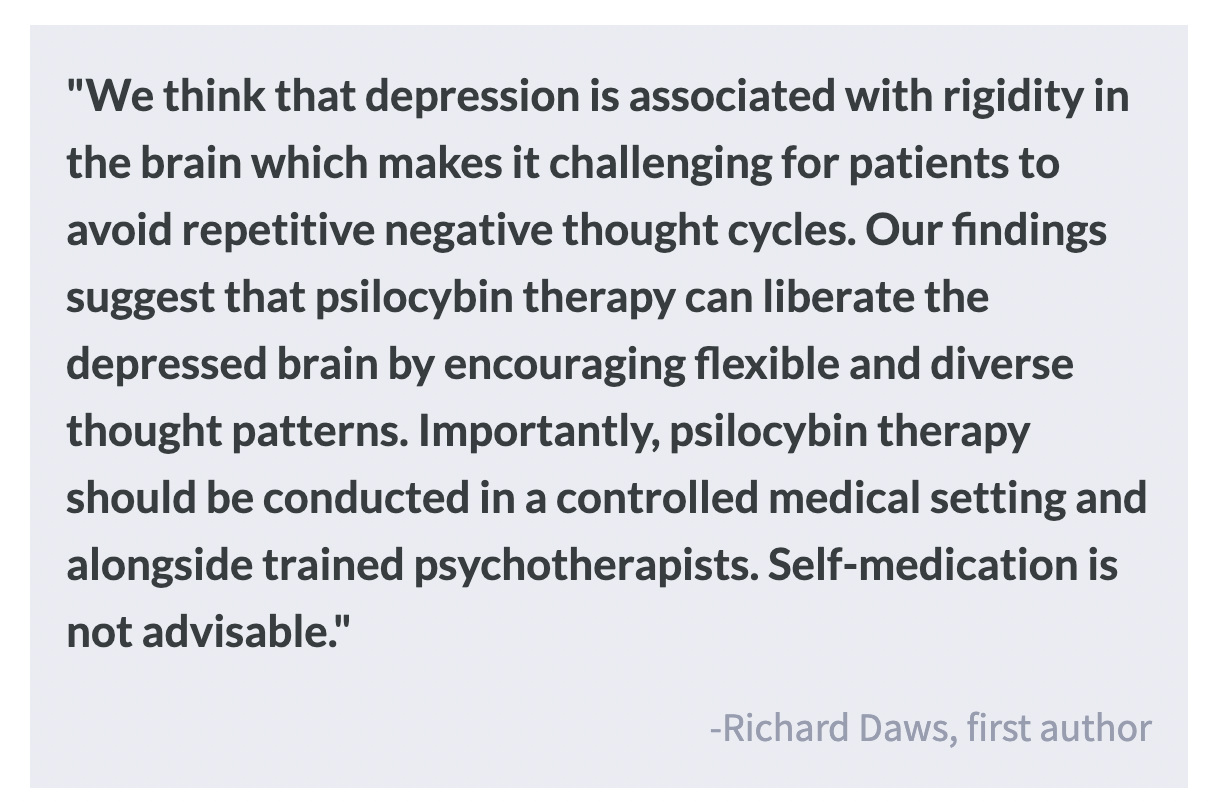

What's the impact?

This study shows that the rapid and sustained antidepressant effect of psilocybin works differently from a conventional SSRI. The brains of patients with depression that received psilocybin became more integrated and flexible, in a manner that is conducive to better mental health and well-being. This work is particularly exciting because the effects of psilocybin on clinical symptoms lasted for up to 6 months in patients who were previously resistant to SSRIs, making it a viable alternative to conventional treatments.