Electrical Modulation Boosts Memory Performance in Older Adults

Post by Anastasia Sares

The takeaway

Electrical neuromodulation, when “dialed-in” correctly, enhanced certain types of memory in a group of older adults. Depending on the region modulated and the frequency of the alternating electric current, participants’ memory of either the beginning or the end of a list of words improved—which could reflect separate boosts in short and long-term memory.

What's the science?

It has been over 80 years since the introduction of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Though its history is fraught with misuse and lack of consent, the technique of electrically modulating the brain has survived to today, becoming more precise, well-researched, and ethically implemented. Nowadays, there are several varieties of electrical neuromodulation, some of which have less intensity and fewer side-effects. They gently modify how neurons fire rather than stimulating new firing. Some of these new techniques are said to increase brain plasticity (the ability for the brain to be malleable and learn new things), which could be especially useful for older adults who are beginning to experience cognitive decline. This week in Nature Neuroscience, Grover and colleagues applied specific electric currents to targeted brain areas in older adults and found that each of these improved memory in a different way.

How did they do it?

The authors randomly assigned their older adult participants to one of three groups: 1) gamma wave modulation (60 cycles per second) above the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (in the frontal region of the brain), 2) theta wave modulation (4 cycles per second) above the inferior parietal lobe (further back in the brain, just above and behind the ears), and 3) a sham condition (where the machine was making noises but not actually passing any electric current).

The modulation (transcranial alternating-current stimulation, or tACS) took place over 4 sessions, with a 1-month follow-up to see if there were any longer-lasting effects. During modulation, the participants tried to memorize lists of words, and their performance was recorded. They did this because it has been shown that doing a task during modulation can improve performance specifically for the networks implicated in the task.

Next, they repeated the whole task, but with a different group of people and with the gamma and theta frequencies swapped for the two distinct parts of the brain (theta in frontal and gamma in parietal), to see if it mattered which frequency was used over which brain area. And finally, they performed a third experiment, similar to the first, to see if their results were replicable.

What did they find?

In people who had the sham condition (no actual brain modulation), performance did not improve (as expected). In people who had the gamma wave modulation above frontal regions, memory for words at the beginning of the lists improved. For people who had theta modulation over parietal regions, memory for words at the end of lists improved. The authors emphasized how these results are consistent with the “dual-store” theory of memory, with recall for the beginning of the lists reflected long-term memory and recall for the end of the lists reflected short-term memory (or working memory).

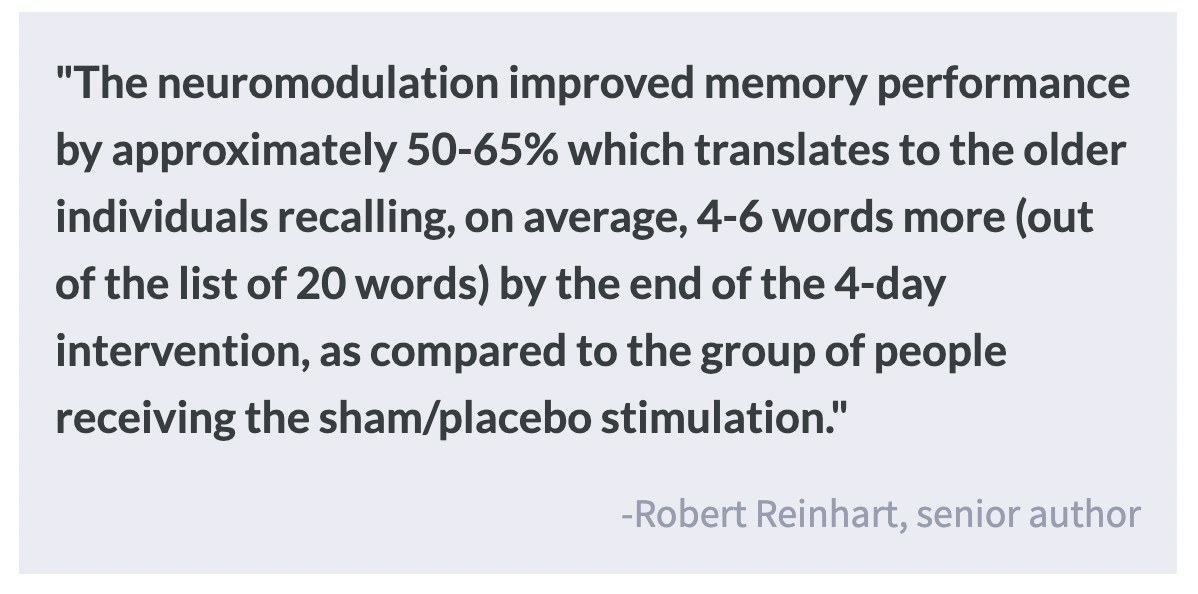

For both experimental groups, improvement could still be seen at the 1-month follow-up. In addition, the greatest benefit was seen in people who had lower cognitive scores to begin with. The findings were replicated in an independent group in the third experiment. In the second experiment where the frequencies were swapped, no memory improvements were observed, meaning that memory performance could only be boosted by a specific frequency of modulation over a specific region of the brain.

What's the impact?

This is an exciting study that shows replicable and lasting effects of neuromodulation on memory in older adults, especially those who have lower cognitive scores. If it can be applied to cases of mild cognitive impairment, before dementia sets in, it could be a revolutionary way to enhance quality of life in the world’s aging population. However, it is important to keep in mind that the neuromodulation had to be paired with a task and repeated many times; it did not offer a global boost to memory capacity.