Biomarkers for Diagnosing Alzheimer’s Disease in the Indigenous Population

Post by Soumilee Chaudhuri

The takeaway

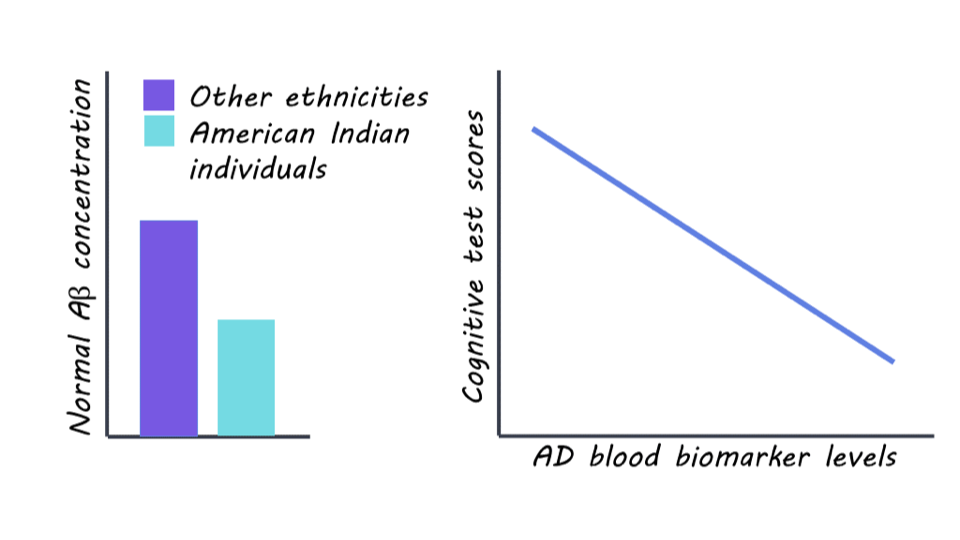

This study reveals unique patterns of blood-based clues linked to Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) in older American Indian (AI) individuals — a critically understudied population in healthcare and biomedical science. Blood-based biomarkers in this population suggest early and more widespread presence of AD-related changes in this indigenous cohort, compared to other ethnic groups.

What's the science?

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia and affects over ~6.5 million people in the United States. As a major public health concern, early identification of AD is important for effective prevention and treatment strategies for this debilitating disorder. However, existing methods of diagnosis such as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis and positron emission tomography (PET) imaging are invasive, expensive, and unaffordable for minoritized populations, including American Indians for whom treatment is often inaccessible due to socioeconomic and systemic factors. Therefore, there is a critical need for noninvasive and low-cost biomarkers that can accurately detect AD pathology, particularly in these underserved communities. The Strong Heart Study (SHS) addresses this gap by investigating blood biomarkers related to AD in a cohort of older American Indian individuals recruited from designated field centers in Arizona, North & South Dakota, and Oklahoma. By examining associations between these biomarkers and clinical, imaging, and cognitive findings, the authors provide critical insights into AD characteristics, diagnostics, and risk factors specific to the American Indian elderly population.

How did they do it?

Initially, SHS recruited American Indian adults aged 64-94 years old from tribal lands in the US Northern Plains, Southern Plains, and Southwest starting in 1981-1991; thereafter, the survivors of this initial cohort were recruited for cognitive aging and AD studies in 2010 ( N = 818) and invited back for a second visit in 2017 (N = 403). Five blood biomarkers of AD including phosphorylated tau (ptau), amyloid beta (A), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), and neurofilament light chain (NfL) were obtained from all participants using designated research platforms. Participants also underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and neuropsychological & cognitive testing (such as memory, executive function, simple and divided attention, etc.). Researchers used statistical methods such as regression analyses and Receiver Operator Characteristics (ROC) to assess the relationships between these blood biomarkers and various imaging measures and cognitive outcomes.

What did they find?

The researchers found significant differences in blood biomarker levels related to AD pathology among the SHS cohort of older American Indian individuals compared to other ethnic groups. The levels of normal Amyloid beta (A) — the lack of which is a hallmark of AD pathology — were significantly lower in this cohort compared to non-Hispanic white (NHW), African American (AA), and Hispanic/Latino populations, indicating a greater degree (almost 3 times) of pathology in this cohort compared to other populations. However, the levels of GFAP and NfL — other biomarkers of AD — were similar in this American Indian cohort as compared to other age-comparable populations. Associations were observed between blood biomarker levels of AD and MRI and cognitive test scores, suggesting potential implications for AD diagnosis and risk assessment in this population. Taken together, these findings reflect that previous studies of comparable risk between American Indian and non-Hispanic White individuals may underestimate AD prevalence in American Indians.

What's the impact?

This is the first study to investigate blood biomarkers for Alzheimer’s Disease in a population historically underrepresented in research: American Indians or the Indigenous people. These findings highlight the importance of understanding cognition and aging in diverse populations facing healthcare disparities so as to improve diagnosis and craft efficient, non-invasive, and affordable treatment strategies. It also shows us that previous studies have severely underestimated the risk of AD in this vulnerable population and urges us to be mindful of recruiting diverse participants from all demographics in AD studies so as to tailor diagnosis and treatment strategies to all.