How Physical Activity Alters the Brain’s Stress Pathways and Cardiovascular Disease Risk

Post by Lani Cupo

The takeaway

One of the ways that physical activity reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease is by reducing activity in the brain’s stress network.

What's the science?

Scientific evidence confirms what many people feel; physical activity (especially cardio) is good for your heart and also helps manage stress levels. The mechanisms underlying these benefits, however, are still poorly understood, and so is the degree to which stress reduction contributes to the cardiovascular benefits of exercise. This week in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, Zureigat and colleagues investigated the underlying mechanisms linking physical activity, stress circuits, and cardiovascular health.

How did they do it?

The authors studied about 50,000 adults enrolled in a Biobank study who filled out a health behavior survey that included details on their physical activity. Information on cardiovascular events (such as heart failure or stroke) and psychiatric disorders (such as depression) before and after enrolment were derived from the electronic medical records. A subset of 744 participants also underwent brain imaging with F-FDG positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT), which provides a marker for regions with high glucose metabolism as a proxy for brain activity. The authors calculated the ratio of PET signal in the amygdala and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (referred to as AmygAc), where a higher value indicates more stress-related activity. They chose to study these regions because they have previously been associated with chronic stress and related syndromes.

The health questionnaires provided information on the history of cardiovascular events (such as heart failure or stroke) and psychiatric disorders (such as depression). The authors used regressions to statistically assess relationships among the variables. First, they examined the associations between physical activity and AmygAc. Then they assessed the association between physical activity and cardiovascular events. Finally, they assessed the association between AmygAc and cardiovascular events. With these sets of equations, they were able to assess whether AmygAc mediated the relationship between physical activity and cardiovascular events. That is to say, whether physical activity indirectly impacts cardiovascular health via stress reduction in the brain’s stress pathways. History of depression was also included as an interaction variable in these models to allow the authors to understand whether patterns in the relationships among the other variables were different for people with past depression.

What did they find?

First, the authors found that physical activity was associated with a decrease in stress-related neural activity, such that the more physical activity participants reported, the less stress-related activity they showed. This was, in large part, associated with increases in prefrontal cortical activity, which may contribute to cognitive health benefits. Second, as expected, they found that physical activity was associated with decreased risk of cardiovascular events. Third, they found that increased AmygAc, representing increased stress-related activity, was associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events. These three findings aligned well with their hypotheses: 1) more physical activity is related to less stress activity in the brain, 2) more physical activity is related to less risk of cardiovascular events, and 3) more stress-related activity is related to more risk of cardiovascular events.

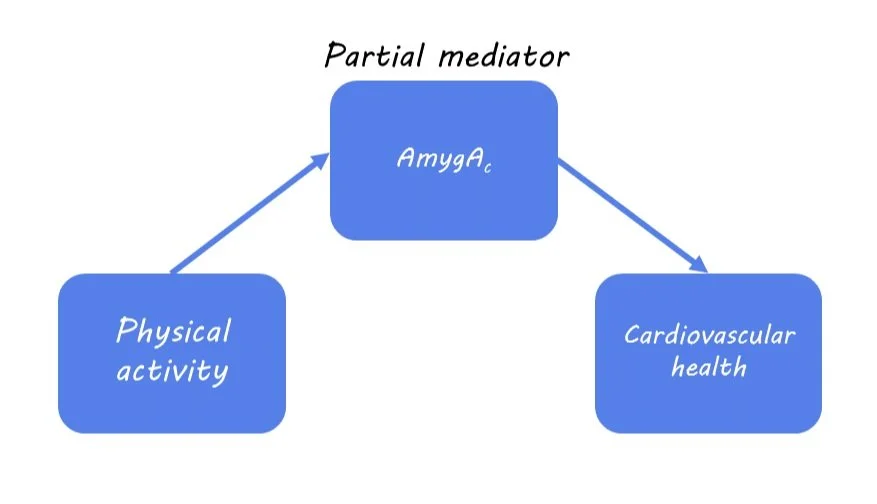

Next, they evaluated whether physical activity lowers cardiovascular disease risk by reducing AmygAc. From their mediation analysis, the authors found that AmygAc was a partial mediator of the relationship between physical activity and cardiovascular events. This means that one way in which physical activity is associated with improved cardiovascular health is by reducing stress, but it’s not the only underlying mechanism.

Finally, the authors found that the benefits of physical activity on cardiovascular health were highest among people with a history of depression. Specifically, people without a history of depression experienced the anticipated benefits of physical exercise, and their risk reductions plateaued at ~300 minutes of moderate-intensity activity per week. On the other hand, people with a history of depression derived roughly double the overall cardiovascular risk reductions compared to those without depression, and continued to derive benefits at the higher levels of activity.

What's the impact?

In this paper, the authors demonstrate that physical activity reduces stress-related brain activity and the risk of cardiovascular events, especially for people with a history of depression. Importantly, reduced stress partially mediates the relationship between physical activity and cardiovascular events, providing an indication of the underlying mechanisms. Future work may further characterize other mediating factors among these variables.