The Link Between Phantom Ear-Ringing and the Brain’s Emotion Centers

Post by Anastasia Sares

The takeaway

Tinnitus is a condition of hearing sound in the absence of any external stimulus, usually a ringing, hissing, or roaring. Though it was initially thought to be purely a hearing disorder related to noise exposure and other physical factors, scientists have discovered surprising connections to emotional and psychological health.

Recently in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences, Singh and colleagues reviewed the literature linking tinnitus to the limbic system: a collection of structures located deep in the brain with functions like spatial memory, threat processing, motivation, and stress. These limbic system connections may explain why tinnitus is related to other aspects of mental health.

What is tinnitus?

There are two prominent theories about the causes of tinnitus. In the first one, lack of auditory input causes the fibers that normally carry auditory signals to fire spontaneously, generating waves of activity that have no outside source. In the second theory, reduced input leads to a lack of inhibition in key auditory areas, which causes an overall increase in auditory signals despite no external sound. In short, in the absence of stabilizing auditory input, brain regions processing sound start to behave differently, going so far as to “invent” signals and interpret them as sound.

Both of these theories highlight the fact that auditory information passes through multiple structures in the brain. Because so many brain regions are involved, there is also the potential for those brain regions to influence the experience of tinnitus. In fact, the experience of tinnitus encompasses both the phantom sounds as well as a person’s reaction to those sounds (conscious or subconscious).

How is the limbic system involved?

We’ll focus on a few prominent brain regions that have been studied in relation to tinnitus.

The hippocampus: this region is tightly tied to the auditory system since auditory information helps with spatial navigation, and the hippocampus is also responsible for long-term auditory memories. Brain scans of people with tinnitus show a decrease in the size of the hippocampus, and activity in the hippocampus can help predict the unpleasantness of people’s tinnitus experience. Since noise exposure can cause noticeable changes in the hippocampus, it may be a key intermediate region in the pathway from noise exposure to tinnitus.

The amygdala: the amygdala is involved in fear and other emotional processing; it also has a strong connection to regions that regulate incoming auditory information. Activity in the amygdala may be a key part of the process that causes stress and negative emotions to intensify the experience of tinnitus.

The nucleus accumbens and anterior cingulate cortex: These are structures involved in motivation, reward, and addiction, and they work against each other. The nucleus accumbens acts to arouse us and orient our attention to both pleasant and unpleasant stimuli, and more neural activity in this area seems to aggravate tinnitus. The anterior cingulate, on the other hand, can help us control and filter out unpleasant auditory stimuli, working against tinnitus symptoms. If this pathway is weakened, it would provide less filtering and thus, stronger symptoms.

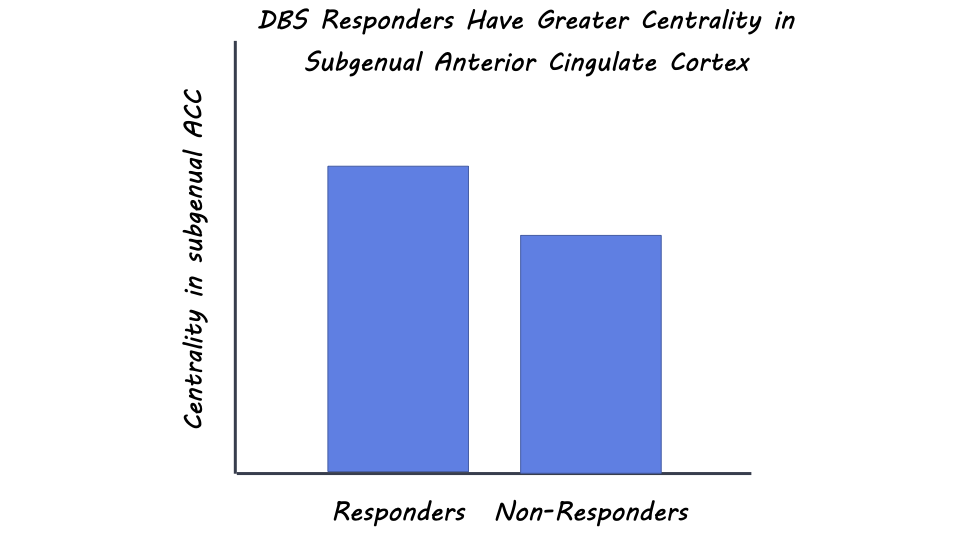

The basal ganglia: The basal ganglia are small regions deep in the brain that form a hub for much of the brain’s activity. How the basal ganglia are involved in tinnitus is somewhat unclear, but there are some dramatic examples of how either stroke or deep brain stimulation in these regions can significantly reduce tinnitus.

What's the impact?

Effective treatments for tinnitus are few and far between, and there is no gold standard. Knowing that limbic regions are involved in creating or exacerbating these symptoms, we can make better guesses at what therapies might work, like drugs that target limbic areas primarily, or deep-brain stimulation in the basal ganglia. Hopefully, more limbic-system-focused therapies are on their way.